How We Calculate Time on Task, the Business Hours Between Two Dates

Measuring the number of business hours between two dates using SQL is one of those classic problems that sounds simple yet has plagued analysts since time immemorial.

This comes up in a couple places at dbt Labs:

- Calculating the time it takes for a support ticket to be solved

- Measuring team performance against response time SLAs

We internally refer to this at "Time on Task," and it can be a critical data point for customer or client facing teams. Thankfully our tools for calculating Time on Task have improved just a little bit since 2006.

Even still, you've got to do some pretty gnarly SQL or dbt gymnastics to get this right, including:

- Figuring out how to exclude nights and weekends from your SQL calculations

- Accounting for holidays using a custom holiday calendar

- Accommodating for changes in business hour schedules

This piece will provide an overview of how and critically why to calculate Time on Task and how we use it here at dbt Labs.

Two strategies to calculate Time on Task

- One size fits all with nested macros

This solution allowed us to create a one-line dbt macro to account for most common Time On Task use cases by having a series of nested macros behind the scenes.

This strategy does a great job in being able to account for nights, weekends and custom holidays, but lacks the flexibility to accommodate changes in business hours, so we've transitioned off of it to the 2nd option:

- Bespoke and customizable with a subquery

Our current production Time on Task calculation is able to be both powerful and flexible by bringing in a construct you rarely see at dbt Labs - a [gasp] subquery. By using an hourly-grain date table, you are able to standardize your organization's unique definition of business hours vs. non business hours in a fully customizable way.

You can find example code for each of these approaches in an example repo.

After we’ve walked through the mechanics of calculating Time on Task, we’ll spend some time thinking about how and why to use this metric in your reporting. Time on Task can be a huge boon for operational reporting, but like any metric it has inherent strengths and weaknesses in terms of reflecting actual business value.

We’ve put together a series of questions to ask yourself to make sure that you are optimizing Time on Task for the problems it is best suited to solve.

The one size fits all solution: nested macros

Our first approach to calculating Time on Task relied upon tying together a series of macros. Specifically, as we diagram below, we needed a way to model non-working time to properly remove it from a standard date_diff calculation.

This approach works great for the case where we have a standard business schedule, but falls flat when we want to bring in more complex, real world applications.

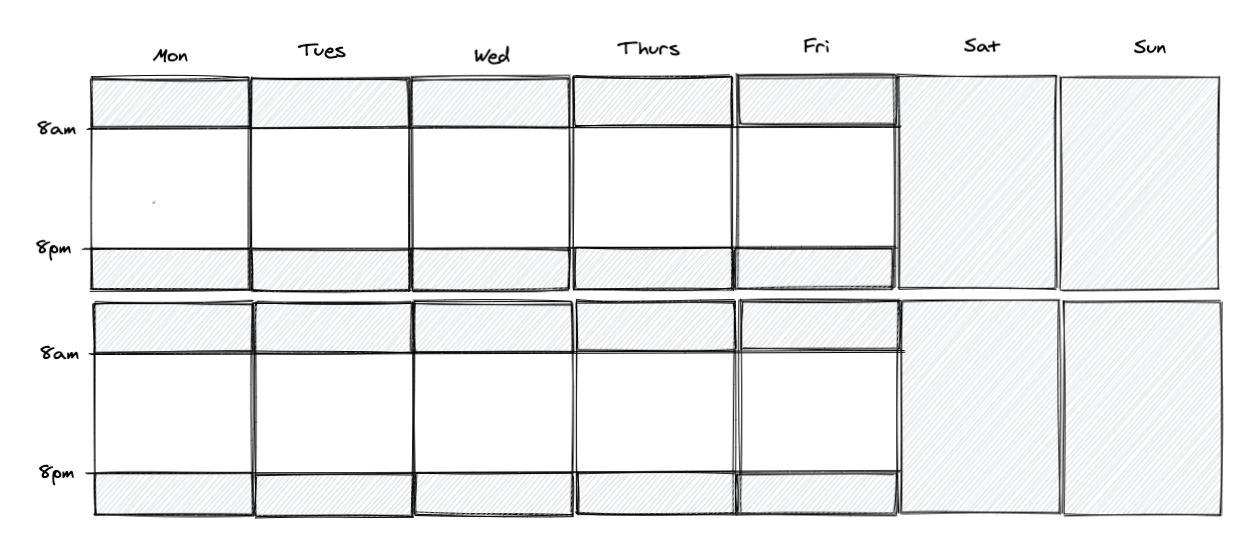

Let’s assume that your customer support team always works Monday to Friday, and from 8am to 8pm, and your schedule looks something like this:

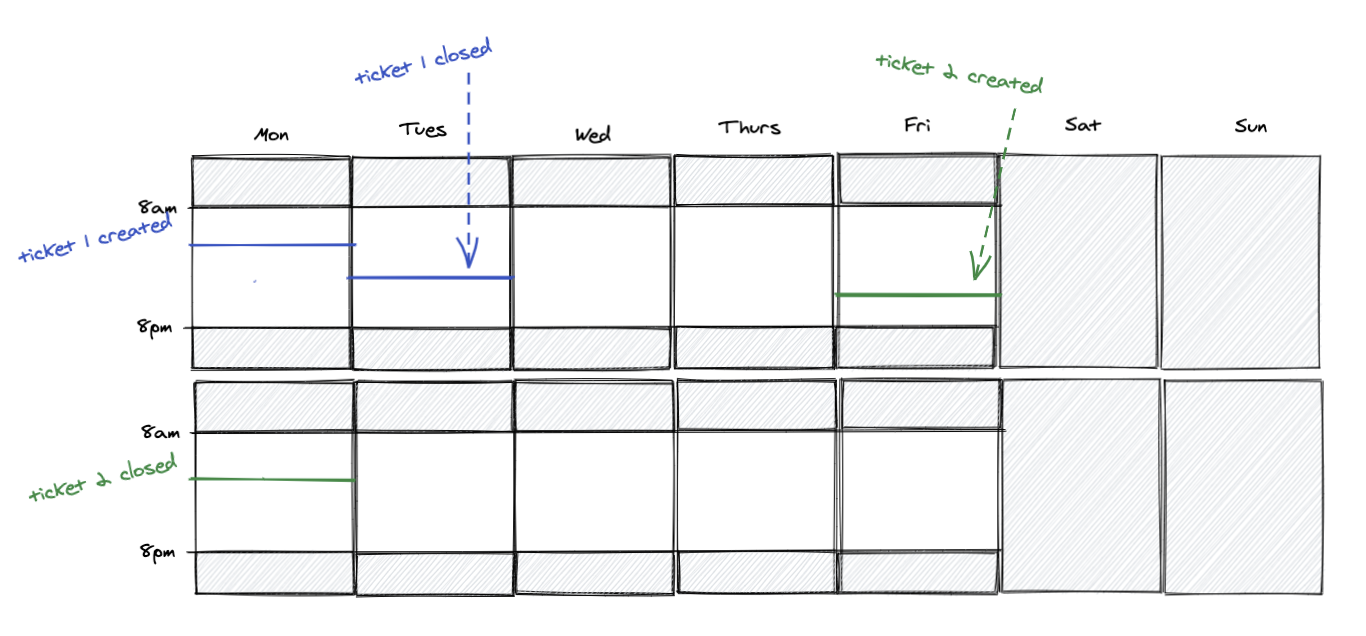

And let’s say you have a few tickets that come in, and your team works through them diligently, as always:

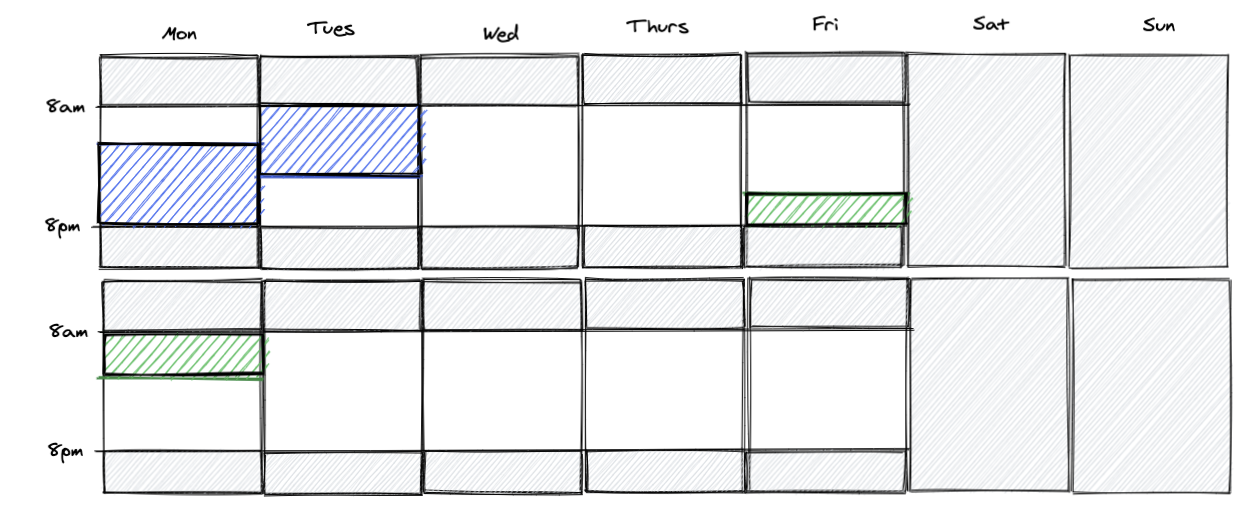

Our schedule-aware metric should only capture the non-grey time:

How do we get there? For any of these tickets, the general formula to get the answer we want can be boiled down to subtracting non-working time from the total amount of time between the dates (i.e. a regular ol’ datediff):

Those blocks of non-working time can be broken down into two sections: overnights and weekends. But how can we dynamically count the number of overnights or weekend days? Enter the weekday macro!

How to exclude weekends?

Building off the excellent work of the intrepid staff over at Looker, we created a macro that returns the number of weekdays between two dates. It works by calculating the number of calendar days between two timestamps, then subtracting the number of Saturdays and Sundays from that result. So, for a ticket created on a Monday, closed on Tuesday, the weekdays_between macro returns 1. For a ticket opened on a Thursday, closed on the following Monday, this macro returns 2!

This ends up being helpful twice - the result of the weekdays macro is the same as the number of overnights between two dates, which is effectively the first half of our non-working time formula. Multiplying the number of weekdays between the two dates by the daily window of non-working time gets us the number of overnight hours (in our example, this window is 8pm - 8am, or 12 hours).

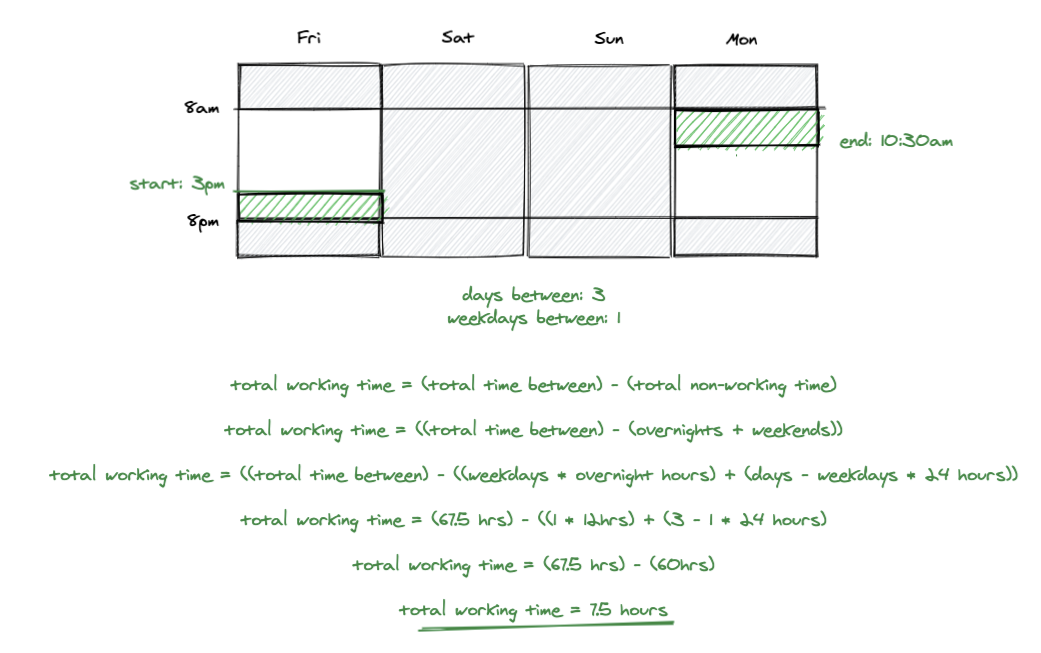

We can use this result to measure the number of weekend days between the two dates – subtracting the number of weekdays from the total number of days between the two dates gives you the number of weekend days. Let’s focus on our example ticket that was opened on Friday and closed on Monday to explain:

You might have already picked up the huge caveat here — a consistent schedule is baked into this calculation, and that’s usually not the case. Throw in a public holiday, or a new hire in a different time zone, and suddenly these calculations stop reflecting reality! Some edge cases and how we deal with them:

What if a ticket comes in outside business hours?

In the past, we had a workaround baked into the ticket table itself! We maintain a all_business_hours model in our project using the date_spine macro from dbt_utils. This creates a table at the hour level, and we add a custom boolean column that indicates whether that hour is within our 8am - 8pm working hour window. We then join this to our ticket data, and for each ticket timestamp of interest, create a new column that returns the next available business hour.

So for any timestamp that is already in business hours like the above example, the timestamp_business column is identical, but for any ticket that comes in outside business hours, it returns the first business hour of the following day - i.e. a ticket made late Wednesday night has a start_business timestamp of 8:00am on Thursday. This allows us to only ever perform these calculations on timestamps that appear within our working hours.

What about holidays?

We maintain a seed file in our project that has the dates of holidays for the next 5 years or so - we join this to our hour-level date_dim table, and incorporate holidays into the boolean column mentioned above. This way, any ticket that comes in on a holiday gets fast forwarded to the beginning of the next working day. Not a perfect solution, so curious to hear how this is handled elsewhere!

The customizable option: a bespoke calendar + subquery

Our first measurement approach recently needed to be adjusted when our business hours changed. It was immediately obvious that this Jenga-tower of macros was too difficult to parse and did not easily accommodate the changes we needed to make. We decided to scrap the whole thing and simplify with the rare (for us!) use of a correlated subquery.

How we accounted for changing business hours

We realized that since we were already maintaining an hourly-grain date dimension table using the datespine macro from dbt_utils, as mentioned above, we could adjust the boolean is_business_hour to reflect the changing schedules over time. Then, we can use the hourly grain table to control the aggregation properly without overly complex macros. The options to accomplish that were:

-

Join directly to the hour-grain table, aggregate after the fact

-

Use a subquery to perform the aggregation

Given that we were actually calculating several of these metrics on one single table of tickets (think: time to first touch, time to first close, time to last touch, etc), direct joining would cause a lot of competing fanout that we decided would be too difficult to manage.

Generally speaking, the dbt Labs team tends to opt for use of CTEs rather than subqueries, but this was one of the few times where the benefits seemed to outweigh the tradeoffs. A subquery allowed us to perform our business hours calculation on any two date fields without changing the grain of our tickets model.

Here’s an example to explain our subquery approach:If working hours for our team are 8AM - 8PM, and a ticket was opened at 8:46 AM Tues, closed 1:13PM Wed on an 8-8 schedule to measure the business hours from open to close, you’d need to include:

-

14 minutes (8:46 AM - 9AM) +

-

16 hours (9AM-8PM Tues + 8am-1pm Wed) +

-

13 min (1PM - 1:13PM)

Which reduces down to:

select

(60 - extract(minute from start_time) +

( select count_if(is_business_hour) * 60 from all_business_hours where date_hour > start_date and date_hour < end_date ) +

( extract(minute from end_time)

from table

What's the value of accurately measuring business hours?

Let’s step back and think about what utility these metrics actually have. What is the benefit of having a schedule-sensitive metric versus just doing a simple date_diff() function and finding the total elapsed time?

I've found business-adjusted time measures to be helpful in a few ways:

-

SLA metrics

- Answering questions like "what percent of tickets are responded to within 15 working minutes?" are great applications of these metrics!

-

Is my staff using their time well?

-

What is the capacity of an FTE to get through the work we have?

-

How many more FTEs will I need to hire to get through the inbound work?

-

Did that process/tooling change I made have any significant impact on how well my team can do their jobs?

What business-adjusted time measures won’t tell you

-

Was my customer frustrated by how long this took? (A ticket might have taken your team a couple hours of working time, but if the elapsed time went overnight or over the weekend, it still feels that long to the customer!)

- If they were, am I communicating the expectations for response time well enough to my customers?

So is there utility in measuring these metrics in a way that takes working hours into account? I think so! But as mentioned in our slack community a while back, doing so in isolation doesn’t give you the whole story of how your customers are feeling when interacting with your team. A great quote from community member James Weakley:

"Any measures that take the support team's schedules into account are process measures rather than outcome measures. In other words, they are very useful for workforce planning or process improvement, but anyone who has logged support cases with large companies will know that they won't correlate with customer happiness as they are far too easy to game."

I totally agree with James here, and think these metrics are most useful when they are answering specific questions about your tools and processes. They can’t tell you much about what the customer is feeling, which is why they should be paired with schedule-agnostic metrics that actually tell you what it’s like from the customer’s perspective (as well as with direct customer satisfaction measures like surveys!).

Special thanks to Claire Carroll and Erica Louie for helping on this work! Some sample data and code for both approaches can be found in this repo.

Comments